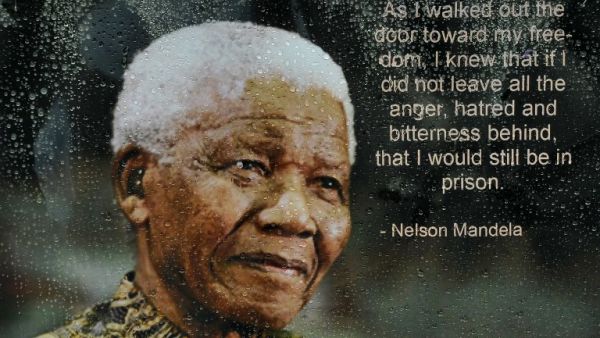

Nelson Mandela’s passing has been felt keenly across the world. With Lebanon, Tunisia and other countries declaring national days of mourning, people across the Middle East have reacted to the loss in a particularly personal way.

Mandela was held in high regard by Arabs for a number of reasons.

Prominent among these was Mandela’s utter commitment to the cause of Palestinian freedom. Since the early days of his movement in 1961, when Mandela came to Algeria to receive military training, Mandela saw the Palestinian struggle as akin to the ANC’s battle against apartheid back in South Africa. He famously remarked that “We know too well that our freedom will be incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians." He held Arafat in high regard and called him an “icon in the proper sense of the word.”

But it is more than Mandela’s support for Palestine that makes him one of the most beloved leaders in the Arab world. For many Arabs, Mandela is more than a leader with a political viewpoint. Mandela is a leader every Arab wishes their country had.

Be it in Syria, Egypt or Yemen, the political landscape of many Middle Eastern countries is characterized by factions with rigid viewpoints who refuse to compromise. They stand gridlocked in their hardline positions and come hard at each other with the politics of “No”. There is much to learn from Mandela - the compromiser who refused to compromise his morals and political journey. It’s a delicate balance to achieve, and one the Middle East desperately needs.

The clashes between the Brotherhood and the military in Egypt are a perfect example of the inflexibility exhibited by those in power and those in the opposition. It’s my way or we’ll unleash the military on you, one party seems to say. It’s my way or a suicide bombing, says the other.

It’s no wonder that the average Arab citizen longs for someone with the largesse of Mandela. Here was a man who forgave his country’s rulers after they had sent him to jail for twenty seven years, even though the majority of these years were spent doing hard labor. Mandela had been made to work in a dusty limestone quarry for much of his imprisonment – during which period his tear ducts clogged up so badly with the dust and grime that he wasn’t even able to cry for many years.

And what did Mandela do upon getting released from prison?

On the second day after his release, he announced that the white people of South Africa had nothing to fear. He forgave those who had imprisoned and tortured him. In forgiving his oppressors, Mandela wasn’t merely being noble. He was also being politically astute. From the example of neighboring Zimbabwe, he saw that a witch hunt against the whites could cause an outright civil war, or make the moneyed class leave the country – a development which would plunge South Africa into a deep economic abyss.

Whether one attributes these actions to a nobility of character or political astuteness, the fact remains that Mandela’s philosophy of compromise allowed his country to step out of the grievances of the past and march onwards to a better future.

It is an example that the battling factions in many Middle Eastern countries could do well to emulate.

If Mandela could forgive the oppressors that had done his people so much harm in the interests of his country, can’t the Egyptian military and the Muslim Brotherhood make allowances and come together for the very survival of their motherland?

Can’t the Syrian rebels be prepared to sit down at the negotiating table without laying stringent preconditions that include “no dialogue with the Assad regime, and President Bashar al-Assad being tried for war crimes?” Can’t they participate in a game of give and take and at least talk to each other to tackle the extremists that threaten to overrun their country? Can’t the Assad regime give up the “we don’t negotiate with terrorists” line of dialogue for the greater good of Syria?

Can’t the Arab nations come together to recognize Israel’s right to exist and jump start talks with the idea of returning to pre-1967 borders (illusory though as it might seem)? Even Nelson Mandela recognized that the formal recognition of Israel as a Jewish state was a prerequisite for Israel withdrawing from the Golan Heights, south Lebanon and the West bank. Or, can’t Israel halt its aggressive settlement building so as not to jeopardize the peace talks?

There are glimmers of hope. Citing Mandela as an inspiration, the Ennahda regime in Tunisia has resorted to dialogue to sort out its problems with the opposition. Earlier this year, the hardline leader of Iran Ayatollah Khomeini called for a “heroic leniency” and encouraged the Iranian government under new President Hassan Rouhani to pursue diplomacy with the West. These are positive developments. But across the region, clearly more needs to be done when it comes to invoking the politics of forgiveness and compromise.

For a large part of the twentieth century and all of this millennium, the Middle East has been plunged in battles that have their roots in age old grievances.

But it’s time to ring out the old. Be it fighting for women’s rights, improving literacy or bettering the education of our children, the new generation should be freed up to battle new problems. We owe them at least that much.

Will a Middle Eastern Nelson Mandela please stand up? In the Middle East, it’s time for the politics of “Yes”.