By Dr. Rene Tebel

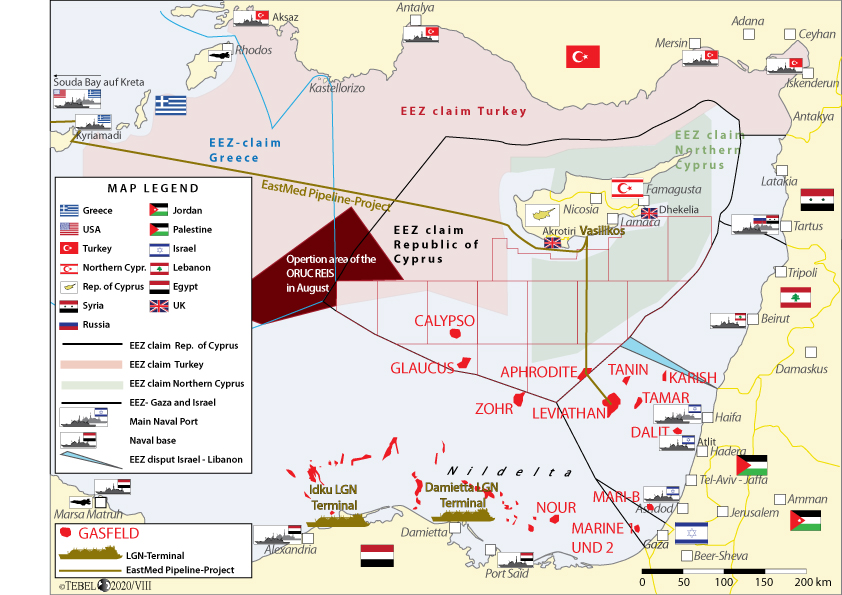

Since Monday, the Turkish seismic research vessel "MTA ORUÇ REIS" has been operating in a sea area between the islands of Crete and Cyprus, which Greece considers its own Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Accompanied by at least 5 warships and its two auxiliary ships "ATAMAN" and "CENGIZ HAN," the "MTA ORUÇ REIS" is systematically looking for natural gas deposits in the region till to the 23rd of August.

Ankara sees this step as a reaction to the Greek-Egyptian agreement on a section of the demarcation of its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) last Thursday. Turkey also intends to further fuel the conflict by planning new licenses for "all sorts of seismic and drilling operations" near the Greek islands of Rhodes and Crete by the end of August, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu announced on Tuesday according to Hurriyet Daily News.

Seismic surveys of Turkish ships are not necessarily new. In an article published in the German business magazine Wirtschaftswoche, Thomas Stölzel analysed the routes of Turkish research vessels between July 2019 and July 2020 using data from Marine Traffic: They show the operations of the "BARBAROS," "YAVUZ" AND "MTA ORUÇ REIS" south of Antalya and east and south of Cyprus as a dense search grid.

Suspected Gas Deposits Require the Establishment of Sea Borders

These voyages also lead to the core of the problem: With the discovery of rich gas deposits in the eastern Mediterranean, the demarcation of maritime borders became a burning question for the Mediterranean states.

And here Turkey does not yet feel adequately considered, as the Turkish president put it in a nutshell according to the Daily Sabah and other media: "There is no way Turkey would consent to any initiative trying to lock the country to its shores, ignoring the vast Turkish territory“ However, Erdoğan is also quoted in the Daily Sabah as saying that Turkey is ready "to resolve conflicts through dialogue on an equitable basis."

The "Exclusive Economic Zone" (EEZ)

In terms of maritime law, the extension of the "Exclusive Economic Zone" (EEZ) is at the heart of the dispute. In addition to the territorial waters, the EEZ was introduced in Montego Bay (Jamaica) in 1982 and came into force in 1994. It may extend no more than 200 nautical miles seawards from the coast.

It grants the coastal state "sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources, whether living or non-living, of the waters superjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and its subsoil, and with regard to other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone, such as the production of energy from the water, currents and winds", as the Convention on the Law of the Sea describes in Article 56.

However, this possibility cannot be exploited everywhere. Coasts and islands are often closer to each other, and in such cases the centre line can be used as a basis. States can also substantiate their claims by bringing into play a continental shelf for themselves, a natural underwater extension of the land area.

Greece bases its legal opinion on Article 121 of the UNCLOS(-III) Convention on the Law of the Sea, according to which islands have a continental shelf and EEZ in the same way as the mainland.

This legal opinion would result in Turkey's EEZ in the Aegean Sea and its southern coast being reduced, despite its long coastline, to a better coastline which, at one point, tapers sharply deep into the Mediterranean Sea.

This is due to the location of Cyprus to the east and Greek islands such as Crete, Karpathos, Kassos and Rhodes to the west. The Turkish claims would be particularly painful in this respect the location of the island of Kastellorizo. The 10 km large island Kastellorizo is only 2 km away from the Turkish mainland in front of Kaş. In the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), the sovereignty went to Italy, but in the Treaty of Paris in 1947, it changed from Italy to its Greek neighbour.

Turkey, one of the few countries in the world not to have acceded to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, in turn assumes that islands generally do not have their own continental shelf and that Kastellorizo is to be considered part of the Turkish continental shelf anyway. In this interpretation, Turkey would in turn cut through both the Greek-Egyptian EEZ and the Greek-Cypriot EEZ.

Map: courtesy of Tebel Report

A Solution in Principle

Thus both counterparts are currently entering into possible bilateral negotiations with maximum claims. One way out, however, is the design of the French EEZ on the island of St. Michel and Miquelon off Canada, but also the Greek-Italian negotiations on the delimitation of their EEZ.

In June 2020, Greece gave up its sole claim in controversial cases - although this was because bilateral agreements from 1977 were taken over - and agreed on a percentage share of the EEZ for islands. The island of Stofades received a 32 percent share, the Diapontia Islands northwest of Corfu a 70 percent share.

Although Greek critics see this as a dangerous weakening of their own position in future negotiations with Turkey, such considerations could ultimately lead to a compromise. However, Turkey for its part would have to recognize the provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and grant islands an EEZ.

This article was republished with the permission of Tebel Report

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Al Bawaba News.