The Complete "Story of Star Wars":

Part 1: "Out of the Past"

Part 2: "Annikin Starkiller"

Part 3: "A Cohesive Reality"

Part 4: "A Desert Planet"

Part 5: "What a Load of Rubbish"

Part 6: "Darth Farmer"

Part 7: "Binary Sunset"

***

Before leaving Star Wars to return to New York, New York—Scorsese had called, needing her because her replacement editor had passed away—Marcia made one last contribution which, arguably, completed the film. It was related to the dogfights.

As a whole, she’d made several important contributions to Star Wars. She had, for example, restored bits and pieces Lucas had wanted to get rid of, like the “For luck!” kiss Leia gives Luke before they swing across the chasm. She may have been the final push an indecisive Lucas needed to kill Obi-Wan, a character who had spent the last third of the film uselessly standing around and whose arc would therefore come to a satisfactory close. She even convinced Lucas to keep the barking robotic dog in the scene where Han Solo and Luke disguise themselves as Stormtroopers.

Yet her most significant contribution was in regards to the Death Star Trench Run scene—officially, the Battle of Yavin.

The cut the editors had assembled reflected the original script. A battle rages over the Death Star: in this long, laborious fight, Luke makes a run for the exhaust port, the Death Star’s weak spot, in order to destroy it, but fails because Darth Vader is in pursuit. It takes him three tries to make the shot because Han is too afraid of Vader to lend a hand. The scene was long, and it was a sludge—completely lacking in the tension needed.

Star Wars is a film dependent on its climax; everything in the story’s intricate subplotting built up to it. This needed to work.

Marcia recut the whole sequence, deciding that Luke would make one run for the exhaust port before firing. If the audience didn’t cheer when Solo rescued Luke, she told Lucas, the film would fail. It had to surprise them.

She also made one last addition: Obi-Wan Kenobi’s spirit telling Luke to use the Force to direct his missile at the exhaust port. The audience would clap, she said. It would an unexpected pay-off to the first act. The move also added a significant layer of mythos to the Force, deepening its impact.

***

One thing in the film did go smoothly.

Lucas went against convention when it came to the film’s score: at the height of disco, he wanted an orchestral soundtrack resplendent with leitmotifs—little pieces of music that were memorable yet flexible enough to recur in various forms throughout the film, associated with theme or character, like the tuba theme which had graced the shark in Jaws.

Lucas hired composer John Williams based on Spielberg’s recommendation. Williams was a tour de force who had crafted a name for himself composing for numerous films and TV series. He’d also won an Oscar—for Jaws.

The Star Wars soundtrack was recorded in March, 1977, over eight sessions at Anvil Studios in Britain, played by the London Symphony Orchestra. Lucas thought that the music should provide an emotional entry point into the film and retain its role as an emotional anchor, so Williams worked to try to give different characters distinct styles of music. Lucas was thrilled; the music exceeded his expectations.

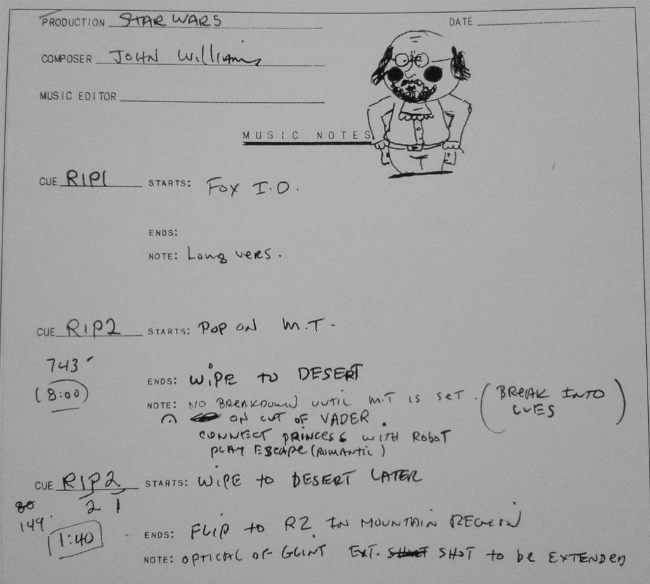

Above: Lucas's doodle of Williams during the recording sessions. (Lucasfilm)

Post-production was somewhat restricted by a car accident Mark Hamill had gotten into. It had visibly scarred his face, limiting reshoots.

But crews did go out to make pick-up shots. The studio, prompted by Ladd, gave the OK-go on an extra $22,000 for second unit shots. Several were needed for Tatooine, filmed at Death Valley and China Lake Acres in California; others were needed for the rebel base, filmed at Tikal, Guatemala, in March of 1977. (Ostensibly, the crew would pay locals with six packs of beer to watch over their equipment.)

ILM also filmed the opening crawl. They lay out the text on the floor, the size of the block around that of an adult’s, and moved a camera longitudinally along. It was a long, time-consuming process, and it took them several tries to get it right.

Chew and Hirsch worked all these new elements into the film. In the end, the editors had lost somewhere between 30% and 40% of Jympson’s footage, and had largely used different takes.

But at long, long last, the film was done.

***

Star Wars was going to fail.

Fox saw it as its “B track” film, which most theatre owners agreed with. Lucasfilm was spearheading its marketing, an effort centred on science-fiction fandom: merchandising tie-ins like Marvel’s comic books and a novelization (credited to Lucas, but actually written by Alan Dean Foster and published by Del Rey) were doing most of the work, a strategy headed by Charles Lippincott. (The novel, for its part, actually sold quite well.)

A booth was set-up at the 1976 San Diego Comic-Con, a small affair with t-shirts available; Mark Hamill was in attendance. Lippincott was there, talking about the film and showing clips to audiences of about 100 people.

A trailer released in December of 1976, and smaller, minimalist posters were available for sale. But it didn’t look anything extraordinary. Things were a bit confused, anyway; the film logo printed on marketing materials was supposedly not even a final design.

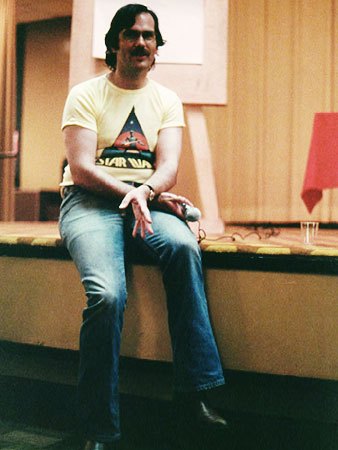

Above: Charles Lippincott wearing a Star Wars t-shirt at the 1976 Comic-Con. (Lucasfilm)

Above: Star Wars at the 1976 Comic-Con. (Lucasfilm)

Above: Star Wars being screened. (Lucasfilm)

Above: Promoting Star Wars at the 1976 Comic-Con. (Lucasfilm)

Above: 1976 Comic-Con Star Wars t-shirt. (Lucasfilm)

Above: A poster from the con. (Lucasfilm)

Twentieth Century Fox’s “A track” feature for that summer was The Other Side of Midnight. It was a highly anticipated film—an almost three hour long adaptation of Sidney Sheldon’s bestselling novel, with the promise of nudity—and Fox tried to extort theatres by saying they wouldn’t give them Midnight unless they took Star Wars, too.

It didn’t really work. Star Wars opened at Mann’s Chinese Theatre in 1977—booked for only two weeks—on Wednesday, May 25th, 1977, and another 31 theatres nationwide. Eight more theatres agreed to show the film Thursday and Friday.

It was a joke.

***

It’s hard to imagine what Star Wars was like on the day.

A small film no-one had heard of playing within the darkness of the theatre. There is a smell of popcorn and fizzy soda in the air. There is no buzz, no hype, no criticism, no real information or expectation. A novelized adaptation has come-out, as has a comic book. The pedigree is Star Trek; others see 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film that hadn’t really made truckloads, as the high watermark of science-fiction films.

Then the Twentieth Century Fox logo plays. It is grandiose with spotlights and an orchestra galore. The music swells to a height...then fades.

And there is silence. A black screen. A held breath.

And then the words faintly appear:

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away....

***

Let us step away in time, just for a moment.

It is 1975. George Lucas is in the middle of his third draft, trying to figure-out what on earth his story is. He has yet to really start production or even a studio’s approval. It is just him and Ralph McQuarrie.

Coppola comes to visit. He has now won multiple Oscars: Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Director. He is master of his own fate. He’s here for business: that Vietnam War film that Lucas and Spielberg had encouraged John Milius to write? It’s on. Coppola wants to produce; ever the mentor, he wants Lucas to direct.

Lucas has yet to really proceed with his innocent, idealistic space film, an anomaly in New Hollywood. He can’t make heads nor tails of his own draft. “I'm not a good writer," he has once said. “It's very, very hard for me. I don't feel I have a natural talent for it.” The Vietnam War film, on the other hand, has been something he’d been planning for years, and, in 1975, President Ford had just pulled the last troops out of Saigon. This would be a timely film.

But something stops Lucas from putting down his pen. Perhaps it is the fact that his film is in some way already an allegory for the Vietnam War: the story of a small force resisting a powerful, technological empire, the small force giving the Empire a run for its money. Perhaps it is the fact that the story, its influences, and the optimism that story represents means something to Lucas, now, in the wake of the Vietnam War’s conclusion, more than ever. Perhaps it is because the story he wants to tell reaches for something deeper than Vietnam. Perhaps it is because he wants to create a myth.

We can never know. What we do know is that Lucas had an interest in mythology and that his approach in writing the film had him break myths down into universal motifs, pinpointing the psychological patterns that lent disparate myths across disparate cultures their timeless, universal appeal. We know that he read the works of Joseph Campbell and drew on them to create his archetypes, as well as the psychological impact those archetypes’ positioning means for the story. We know that Campbell’s work influenced Lucas into boiling down his sprawling plot into the basic “hero’s journey” arc, that it influenced him in finding the essence of myth. We know it was a far cry from what New Hollywood was doing, or what the Vietnam War film could have let him achieve.

Above: Journalist Bill Moyers and author Joseph Campbell sit down in The Power of Myth (1988). (PBS)

Above: From Idylls of the King, illustrated by Gustave Dore.

Above: Battle of the Doomed Gods by Friedrich Wilhelm Heine (1882)

Above: Battle Between Lapiths and Centaurs, by Giordano Luca. (late 1680s)

The truth is obscured, perhaps even to him. But there is a shot in Star Wars which I’ve always maintained is the key to the film’s appeal: Luke, upset that he’ll be spending another year living in the middle of nowhere, goes outside, frustrated, in order to contemplate the sunset. It’s an action and sentiment familiar to most people, but there’s a twist: there are actually two suns setting over the horizon. Familiar, yes, but so indelibly powerful and so indelibly strange—like a myth.

And as for that Vietnam War film? It would eventually release after an insane production of its own as Apocalypse Now (1979), directed by Coppola. It was his fourth consecutive masterpiece in a run that included The Godfather (1972), The Godfather, Part II (1974), and The Conversation (1974), and is now ranked among the greatest American films ever made.

Above: Apocalypse Now (1979). (United Artists)

***

Star Wars was going to fail.

The cast and crew who watch the film do so with low expectations, bewildered by the building hype. They, too, sit in the darkness of the theatre. They, too, wait.

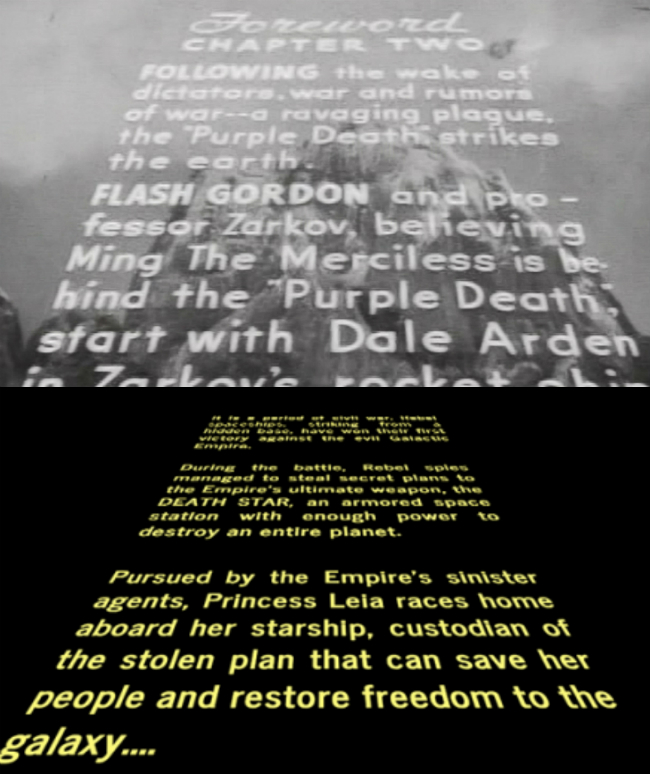

And then the music takes over and everything changes. The crawl emerges, a quarter of its original size...the first positive sign, credit to Brian De Palma and Jay Cocks. It scrolls up towards a vanishing point, just like Flash Gordon.

And then the horizon.

And then the ships in space, going in pursuit.

Above: The opening crawl from Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940); the opening crawl as it appeared in the 1977 Star Wars. (Universal Pictures/Lucasfilm)

The cast and crew were shocked. Lucas had been true to his word; he had gone and fixed everything. The Mos Cantina on-screen was a far cry from its appearance on set; Lucas had used post-production to shoot close-ups of various aliens at Elstree after principal photography had wrapped-up. Darth Vader? Darth Vader was terrifying.

But the film didn’t just look good; it was good. People were cheering, whistling, applauding. People were coming-up to crew members—model-makers and technicians—to ask for autographs. Harrison Ford realised his life had changed when he was mobbed by fans at a record shop; they were so frantic they tore his shirt off. Fisher began driving around Mann’s Chinese Theatre, shocked by the waves of people coming to see the film.

What. The. Hell, they thought. What. The. Hell.

***

Star Wars was going to fail.

Lucas and Marcia were going to avoid the fallout by going to Hawaii. It’d be a nice, well-deserved holiday. In the lead-up, they were spending time together at MGM studios; Marcia was overseeing the sound editing on New York, New York while George was mixing sounds on foreign versions of Star Wars. They mostly saw each other as shifts changed (“Hey,” he’d say; “Hey,” she’d say, passing) and over lunch.

It was during one of these lunch breaks that they passed by Mann’s Chinese Theatre and spotted a huge line forming. Curious, they approached, only to see that the film people were lining-up for was, of all things, Star Wars. It had opened. They’d forgotten. The science-fiction audience must have been forming-up.

A phone call came through from Ladd before Lucas went off to Hawaii. People were talking about Star Wars, he said. The first reviews were glowing. Maybe the film had a chance. Lucas put it out of mind and went to the airport.

Spielberg and Amy Irving—now a couple—followed Lucas and Marcia to Hawaii, bringing with them news of the kind of traction Star Wars was getting: people were clamouring to see it, and it was opening in more and more theatres. Ludd himself was calling every night with new numbers: the film was breaking house records. Again, Lucas didn’t let himself believe; it was a sign that maybe the film wouldn’t completely tank.

More and more theatres began requesting the movie. More and more people went back to it, to see it. Its stars were becoming household names; Mann’s Chinese Theatre would take the unprecedented step of bringing Star Wars back for a second opening on August 3rd, 1977, by which point the film had been playing at 1096 theatres across the US; R2-D2, C-3PO, and Darth Vader all placed their footprints in the theatre’s forecourt at the ceremony. Thousands of people showed-up; Star Wars, Fox realised, really had gone beyond its supposed science-fiction audience.

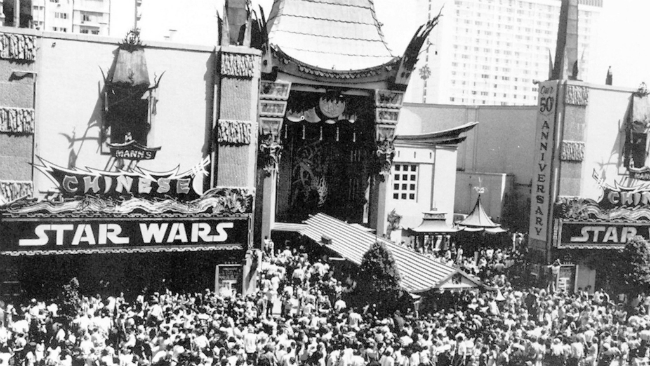

Above: Clamouring to see Star Wars in 1977. (Mann's Chinese Theatre)

It’s the smaller details that indicate how big a movie it became. Coppola, now about to make Apocalypse Now, contacted his former protégé Lucas for money. Spielberg reportedly won a cool $40 million off his little bet, a promise Lucas kept. And Guinness? Alec Guinness, for his part, revealed nothing. But his 1985 autobiography did provide one insight into his fortunes:

“Blessed be Star Wars,” it said.

***

Star Wars was going to fail.

Despite the word he was getting, Lucas didn’t really think anyone would take to his film. It had been too consistently mocked, too often dismissed, for it to resonate.

Then one night he turned on the TV—Ladd had called him in the middle of his second week of holiday, begging him to switch to CBS—to find Walter Cronkite, the Walter Cronkite, doing a report on Star Wars. It wasn’t growing; it had become a sensation.

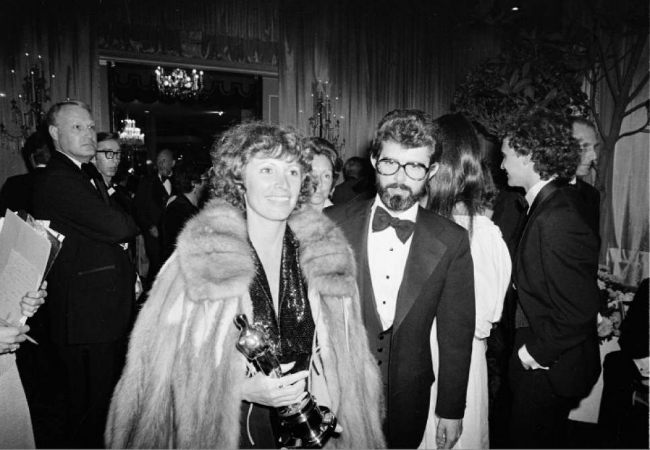

Star Wars hadn’t set records as one of the highest-grossing movies ever made yet—an accolade it holds to this day. It would be a while before it would be nominated for ten Oscars, winning seven, including Best Editor for Marcia, Chew, and Hirsch; a while before its earth-shattering box office success allowed Lucas and his lawyer Tom Pollock to retake its merchandising rights from Fox for the promise of a sequel, a while before Lippincott’s efforts would topple New Hollywood, driving it from a film industry into the merchandise-driven, franchise-obsessed empire it is today, a while before Mark Hamill and Carrie Fisher would grace the fronts of cereal boxes and be shaped into Pez dispensers. It would be years before Guinness began grumbling publicly about how Star Wars had overshadowed the rest of his career, years before Lucas would create the prequels which would diminish the Star Wars name, years too before he would sell his company to Disney and retire and publicly lament how the company disregarded his ideas for the sequels they would produce.

No: in that moment all he saw was a line of people, so long it wrapped around the block, waiting to see the movie he had fought tooth and nail to make.

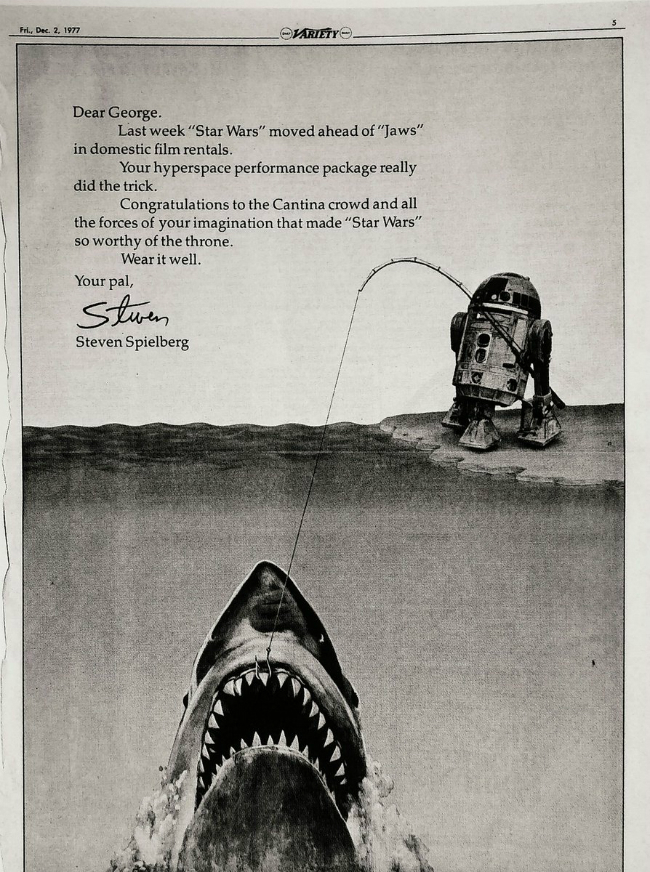

Above: Spielberg congratulated Lucas by taking out an ad in Variety. (Variety)

Above: Marcia wins her Oscar. (AP)

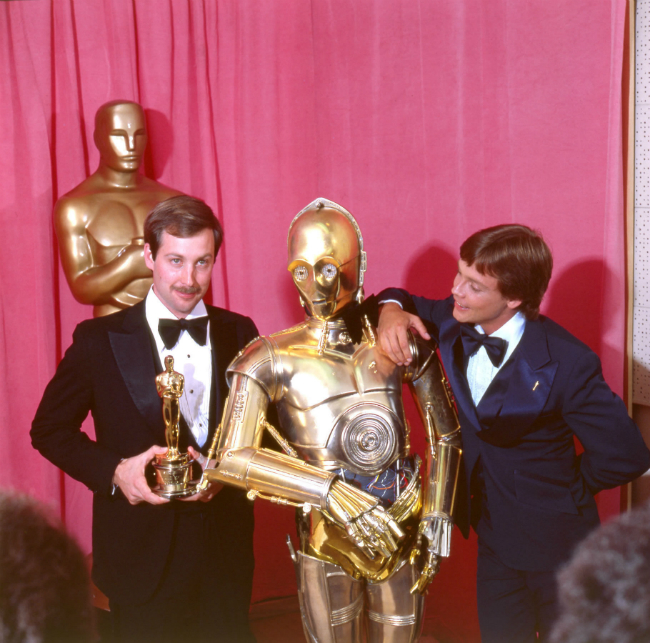

Above: Ben Burtt, C-3PO, and Mark Hamill. (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

***

It's hard to imagine what Star Wars was like on the day.

But it’s not impossible.

I have a four year old cousin. She’s at that age where she’s just graduating from cartoons and beginning to develop an interest in live action material. She’s also largely free from nuance in her assessments, in the way most children are: things are either good, or they’re bad. There’s no quantifier.

She’d heard about Star Wars—Rogue One and The Force Awakens had made a splash. But she hadn’t seen it. Was she willing?

No, she said. She’d rather watch My Little Pony.

Please?

No.

Just five minutes?

OK, she said. But just five minutes.

It's hard to imagine what Star Wars was like on the day. But when the music swelled and the rebel ship got hit by that Imperial Destroyer, lasers blazing and sparks flying, she sat-up, eyes wide.

“Woahhhhh," she said. And on the next day, she asked for seconds.

Written by Karim Anani for Al Bawaba