The Complete "Story of Star Wars":

Part 1: "Out of the Past"

Part 2: "Annikin Starkiller"

Part 3: "A Cohesive Reality"

Part 4: "A Desert Planet"

Part 5: "What a Load of Rubbish"

Part 6: "Darth Farmer"

Part 7: "Binary Sunset"

***

The ILM team had been busy, meanwhile, in Hertfordshire, preparing props and sets in Elstree Studios over several months. Elstree was massive, chosen for its size as well as its access to top-of-the-line construction crews; it would also let Lucas to make free use of its personnel.

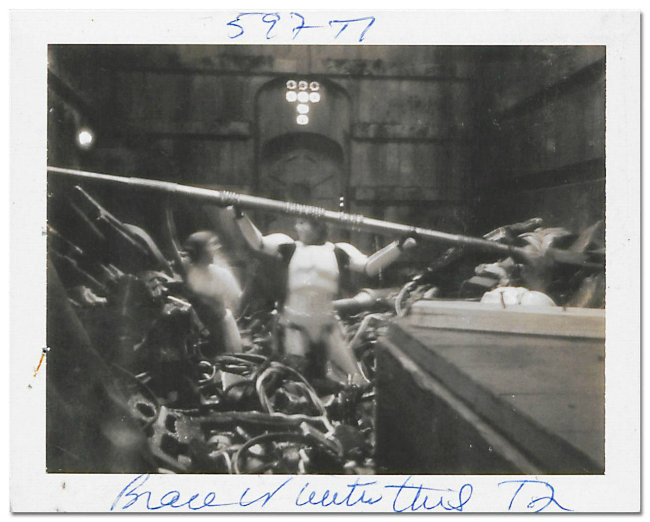

Among these sets were the Millennium Falcon, built from the scrap metal gathered; a trash compactor, full of water and carefully weighed, bobbing pieces of rubbish; and the insides of several space stations, including the Death Star, a deep space battleship with the firepower to obliterate a planet.

The cast and crew arrived at Elstree slightly more optimistic—no more heat, no more freak rainstorms. It felt like a whole new movie—Fisher, Prowse, Ford, and Mayhew joined the production, finally bringing all the cast together, the sets intricately built and populated by aliens and extras in-costume. An intimidating Darth Vader appeared for the first time. So the cast went onto the breach more optimistic, even when they found-out that British union rules meant that, unless Lucas was in the middle of a shot, production had to stop everyday at 5:30 pm.

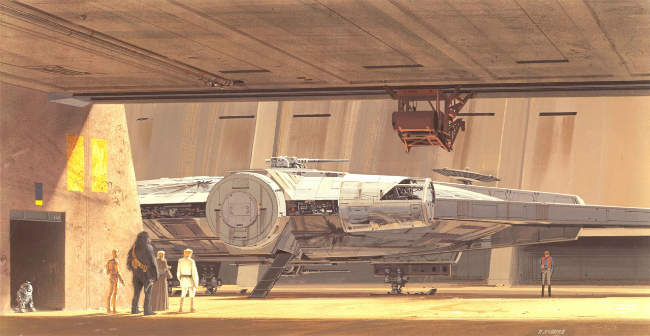

Above: The Millennium Falcon as depicted by Ralph McQuarrie. (Lucasfilm)

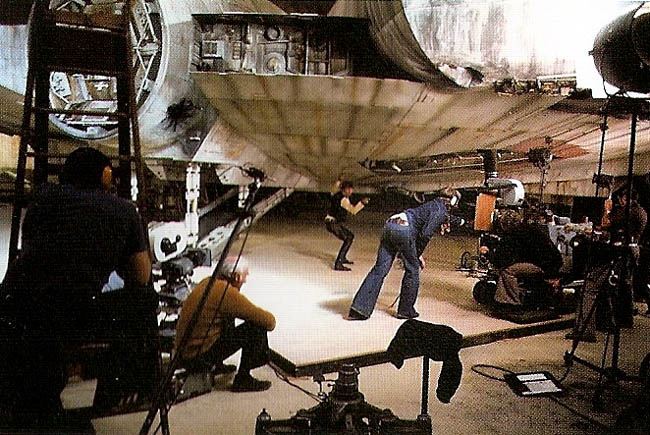

Above: The Millennium Falcon as it was on set. (Lucasfilm)

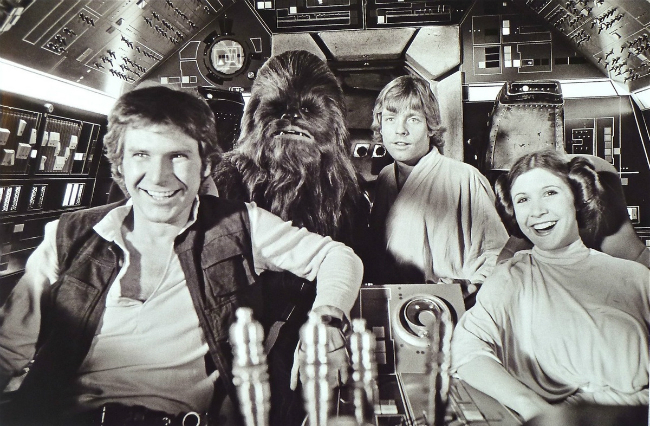

Image: The interior Millennium Falcon set. (Lucasfilm)

But the British crew, largely absent from Tunisia, were bewildered by the film—they didn’t understand it, were apathetic towards it, and therefore never took their work seriously. Their attitude was infectious.

“I’m not putting down the British crew,” Anthony Daniels later said, “but there was kind of an attitude like, ‘Pfft, what is this?’”

The dialogue was a mouthful. Prowse, for all his size, wasn’t a very intimidating Darth Vader, speaking in a soft West Country accent which earned him the nickname “Darth Farmer.”

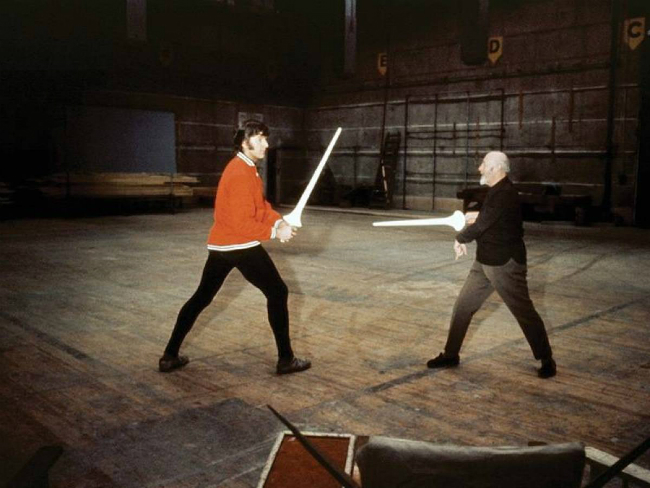

“Sword fights” were being done with poles and rods covered in retroreflective sheeting, most of which Prowse kept breaking.

In several scenes, Stormtroopers—the Galactic Empire’s boots—were unable to walk through doors, often stumbling and collapsing in a heap on the ground. (In one shot, which remains in the movie, a Stormtrooper rushing through a doorway bumps his head on a low ceiling clearance. The Special Edition of the movie commemorated this editing oversight by adding a boink sound to the scene.)

Everyone was confused as to what the hell was going on.

Above: A thrilling stick fight. (Lucasfilm)

A good case study for this is the Mos Eisley Cantina sequence—an important part of the film where audiences meet Han Solo for the first time and Obi-Wan Kenobi reveals a more ruthless side to his personality.

“It was very imaginatively described in the script,” said Mark Hamill. By contrast, the sequence on set was underwhelming: an array of animal-human hybrids reminiscent ofEuropean art-house. Lucas tried to placate his actors’ concerns, saying he’d fix everything, but they were doubtful. There wasn’t a lot to see: a lot of the movie as it existed looked cheap and weird on set. The horrifying sequence in which the Death Star blows-up the planet Alderaan was just a guy waving his hand behind a screen and yelling, “Bang!”

Above: "Alderaan is going to be there. We'll make it go boom." (Lucasfilm)

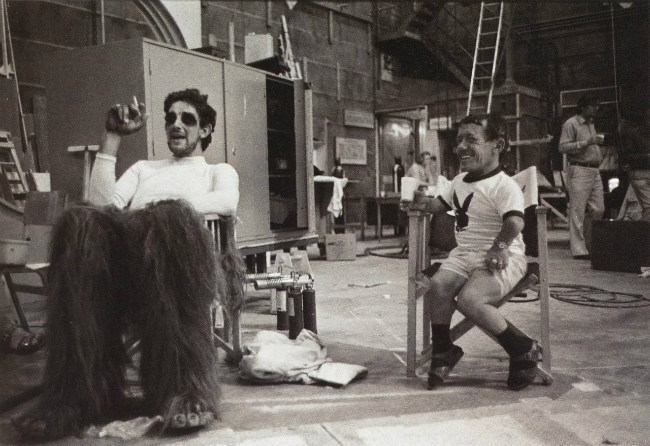

Above: A robot and a giant in a monkey suit. (Lucasfilm)

Above: A confused and grumpy-looking Han and Chewie. (Lucasfilm)

The crew’s sneering pessimism became ubiquitous. Between all the malfunctioning props and effects, the lines that made no sense and the strange, cheesy alien costumes, everyone became more vocal with their attitude towards the film. Harrison Ford didn’t understand why he was acting alongside a “giant in a monkey suit,” saving a “princess with weird buns in her hair.” Kenny Baker brought-out that old word: “Rubbish.” The crew indicated the depths of their disdain when they refused their director the extra fifteen minutes he could legally ask of them after 5.30 pm—always, and without exception.

It began weighing on George Lucas, a man who had spent years writing his script, had fought tooth and nail to get the production started and spent his own money to get design going only to end-up being isolated in his film. His frequent clashes with Taylor didn’t help. He became withdrawn and shy, at one point losing his voice for several days before the actors noticed. He seemed to have little patience for the nuances of acting, anyway: his one direction to actors was to say “faster” and “more intense.” This became something of a running joke on a set filled with running jokes, prompting the actors to consider getting him a board with the instructions printed on it to save him time.

Fisher and Hamill—who enjoyed pranking each other on set—began to try pranking Lucas, something which amused the cast and crew.

“We were all goofing around,” said Hamill, “trying to make George laugh. Because he really looked like he was ready to burst into tears and you would try and cheer him up.”

The reports coming in from the studio weren’t helping Lucas, either—changes to a screenplay barely anyone understood were one thing, but costs were ballooning. Executives began making helpful notes to improve the film; one memorable suggestion wanted Chewbacca, a space bigfoot with a gun, in trousers.

Above: "Brace it with this!" from the trash compactor scene. (Ann Skinner/Lucasfilm)

The production stopped being able to afford stunt doubles. In one scene towards the end of the film, Luke and Leia need to cross a chasm on a rope—a dangerous stunt that on another set would be done by professionals. The actors would have to make a run for it, and god bless the production if something happened to them. The day came. Lights, camera, action: Fisher grabbed Hamill, Hamill held onto Fisher, the actors ran, swung across the chasm, and the harness held; in a rare stroke of luck for Lucas, Hamill and Fisher managed it in one take.

Few realised how depressed Lucas had become. With the benefit of hindsight, it is obvious that the film meant a lot to him: the movie, he would later say, was “the flotsam and jetsam from the period when I was twelve years old. All the books and films and comics that I liked when I was a child.” It was a deeply personal tribute to things he loved and which, now, in the middle of his own production, were subject to scorn. He would try to fight the crew’s pessimism to little or no avail. Problems were sprouting at ILM, a venture costing Lucas something like $25,000 a week. Lucas was also going into the editing room on weekends. A problem had also developed with the editing: the first cut of Star Wars, assembled by John Jympson, confirmed every fear and shred of scorn that had been laid on the film. In Lucas’s own words, it was a disaster.

It was a lethargic, incomprehensible mess. Jympson had cut the film in a traditional manner: master shot intertwined with close-up coverage. And his choice of takes wasn’t always ideal, either. Lucas was coming in on weekends to recut it in a style he hoped Jympson would take to. It didn’t happen, and Jympson was dismissed from the project. Lucas was left stranded without an editor in the midst of a difficult shoot that had abandoned its calendar to the winds.

The pressure was mounting. Lucas’s health deteriorated. During a visit to California, he began feeling severe pains inside his chest; Marcia rushed him to Marin General Hospital, where doctors diagnosed him with hypertension and exhaustion. He needed to take it easy, they said. He was putting himself at risk.

And still the production went on.

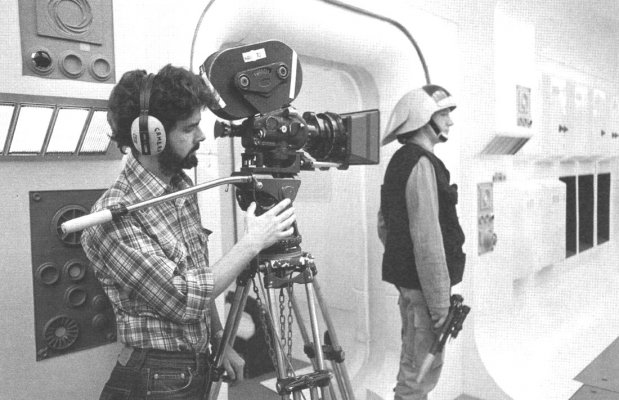

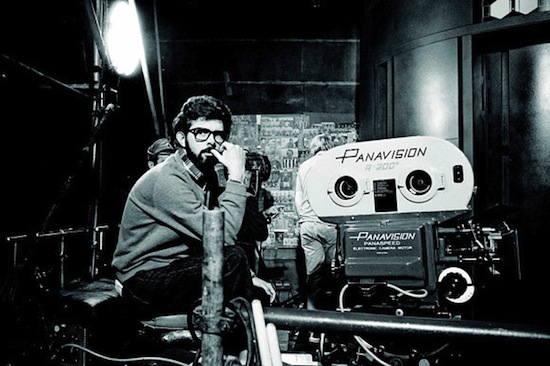

One silver lining did come in the form of Gilbert Taylor. When he’d walked into Elstree, Taylor had proclaimed that John Barry’s sets were too dark—“like a coal mine." Lighting them was going to be a problem. He took an axe to the walls, ceilings, and floors, then installed a system of quartz lamps to use as panel lighting. This ended-up being beneficial for Lucas: he could shoot a scene how he wanted, with a lot more freedom, without having to worry too much about relighting a shot, facilitating production.

Above: Filming in Elstree. (Lucasfilm)

But things finally came to a head in the last week of shooting. The filmwas supposed to launch in Christmas of 1976, but work had gone extensively behind schedule and prompted a changed date, now to the summer of 1977. Fox executives didn’t take kindly to Lucas’s request for more money, either; the entire production, Ladd told Lucas, was threatened with shutdown. He had one week until the next board meeting to say that shooting had wrapped.

The pressure reached breaking point. Production split into three units: one led by Lucas, who would get on his bicycle and rush between sound stages; another by producer Gary Kurtz; and the last led by Robert Watts. Together, they got the shots they needed, though at much higher expense. Principal photography stumbled across the finish line with barely a moment to spare.

***

One important actor had spent the shoot thinking it was a load of rubbish. But he hadn’t said so.

Alec Guinness—Sir Alec Guinness—had pedigree. Star Wars had appealed to him partially because he saw it as a morality tale; but to work on the film, he’d made a deal with George Lucas to earn 2.25% of gross royalties paid to the director—meaning that, to some degree, he must have believed in it—as well as double the salary he’d originally been offered. It was good money.

Secretly, he was confused and irritated. In a letter to a friend, he described the film as “fairy-tale rubbish,” albeit “interesting.” He dismissed the “rubbish dialogue” he was given, lamenting how none of it revealed anything about his character or was “even bearable.” Worst, for him, was how old he felt: “I find myself old and out of touch with the young.” In another letter, he added, “Oh, God, God, they make me feel ninety – and treat me as if I was 106.”

But little of this seems to have made it on set—Guinness was nothing if not a professional. Hamill, Ford, Fisher, Baker, and Daniels all singled him out for his work ethic and his courteous manner both on and off set. “It was, for me, fascinating to watch Alec Guinness,” Harrison Ford would reflect later. “He was always prepared, always professional, always very kind to the other actors. He had a very clear head about how to serve the story.”

Above: Guinness and Prowse rehearsing their fight. (Lucasfilm)

Above: Lucas directs Sir Alec during his duel with Vader. (Lucasfilm)

Lucas himself credited Guinness, saying his encouragement of the cast and crew contributed to the completion of the film.

“He was the one who brought [the production] some sort of legitimacy,” said Hamill. It is safe to say that, without Guinness,the movie would have never wrapped.

***

There were other major details that changed during production.

One was about a character. Luke, Lucas had decided, would be renamed: Luke Starkiller to Luke Skywalker. The second change was to the film’s title. The Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Starkiller became The Star Wars. The Star Wars went through one more change:

Star Wars, Lucas decided he would call it. It would simply be called Star Wars.

NEXT: "Darth Farmer"