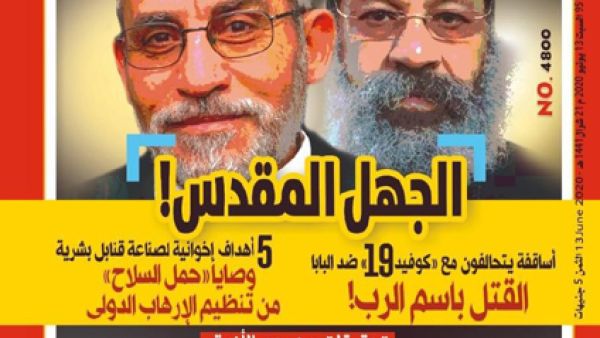

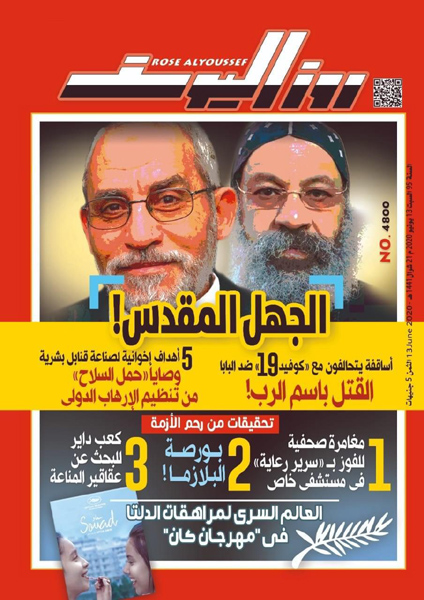

Controversy erupted after Egyptian state-owned magazine Rose al Yusuf published a cover photo of Bishop Raphael, the general bishop and secretary of the Holy Synod of the Coptic Orthodox Church, next to Mohammed Badie, former Supreme Guide of the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood.

Under the title “Holy Ignorance,” the magazine published the cover photo in its issue last Saturday, prompting an official statement by the church upon Pope Tawadros II’s orders denouncing the cover.

“The cover photo of the magazine’s weekly issue is offensive to the Coptic church,” said the statement, adding that the church decried how the bishop had been put on “the same level with one of the country’s traitors.”

“This is not considered freedom of expression. It is rather a serious abuse and transgression that must not pass without accountability from the authority responsible for this magazine,” it stressed.

Following the church’s statement, Egypt’s National Press Authority on Saturday referred the editor-in-chief of the magazine for an investigation and apologised to the church, saying that the Rose al Yusuf will publish an apology in its next issue.

Journalists have argued that punishing a magazine merely because it spotlighted a sensitive issue inside the church carries a message of intimidation to the media, and gives the impression that religious institutions are immune to criticism.

Controversy deepened after Egyptian State Media and Information Minister Osama Heikal was blamed on state TV for failing to adequately address the situation.

“The Minister of Information is not required to be a school teacher dictating instructions to us and determine what we should be saying, but rather setting a media policy,” said journalist Wael al-Ebrashy, who conversely praised the professionalism of the head of the National Press Authority, Karam Jabr, for quickly intervening to help resolve the dispute.

Some considered Ebrashy’s remarks as a way of settling scores. A few days earlier, Heikal criticised media workers in Maspero (the headquarters of the Egyptian Radio and Television Union) and their development plan.

Safwat al-Alem, a professor of political media at Cairo University, said “the inclusion of the Minister of Information in the crisis of the church and the magazine and the attack on it has nothing to do with freedom of expression, and falls under intentional phishing.”

“The parties that monopolise the management of the system feel that they are stronger than the minister, so they attack him under the pretext of his failure to set a media policy for the state,” Alem added.

Observers said Heikal’s problem is that he lacks the power to impose sanctions on journalists or editors. Ebrashi criticised him because he knew the minister would be unable to react, for fear of being accused of using the powers of another authority – the National Press – or of exacerbating a crisis between the media and the church.

“Conflicts in roles between the Ministry of Information and media institutions will not end before the latter is canceled. Every president of one of these institutions considers himself immune from interference in his policies, which restricts the Minister of Information from moving one step forward”, said Sami al-Sharif, former president of the Radio and Television Union.

This article has been adapted from its original source.