“In 1981, at the 1979 Gallery, we had an exhibition,” Palestinian artist Nabil Anani recalled, “but it was closed down completely with red tape and they wouldn’t let us open for five months. They saw we had so many people coming to the gallery and that we had an influence. They sent us to the Israeli intelligence.

“When we went to the very high-ranked official, he said ‘You are working the gallery against the state, and if you keep working against the state we will take further action,’” the artist added.

“He said we’re not allowed to use symbols against Israel and he focused on the flag - even the colors of the flag, even if it is a flower with the different petals showing each color of the flag, this is prohibited.

“Our friend Issam said, ‘What if I want to paint a watermelon?’ The man said ‘Yes, I suppose you can do that.’ Naturally we ignored the official and painted whatever we wanted.”

Dar El-Nimer for Arts and Culture and the Institute for Palestine Studies recently gathered Anani, and his colleagues Sliman Mansour, Tayseer Barakat and Vera Tamari for a talk to launch their group exhibition on the evolution of Palestine’s modern art movement.

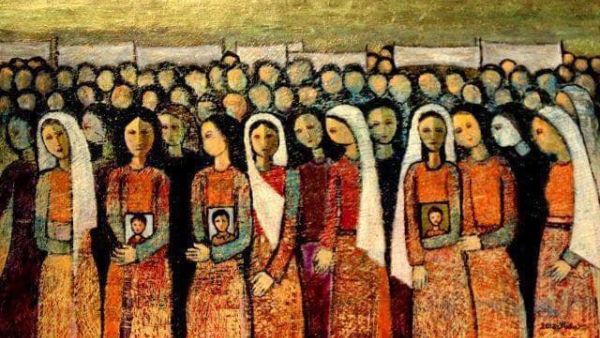

“Challenges of Identity” is the first Beirut group exhibition of these artists, who are considered four of the founding members of the Palestinian modern art scene. The show draws on pieces from the artists’ private collections, the Nimer Collection and that of Rula Alami.

The group came together in response to the First Intifada (1987 -1991) and founded New Visions, an organization seeking to address freedom of expression and create a support network for Palestinian art. Looking back, the group discussed the challenges and changes they faced as artists in an occupied land.

“When we started we were very young, in our early 20s,” Mansour recalled. “We founded [the group] in 1974-75 and had our first exhibition in Jerusalem, which then moved to Ramallah, Nablus and Gaza. The exhibition made a great impact.

{"preview_thumbnail":"https://cdn.flowplayer.com/6684a05f-6468-4ecd-87d5-a748773282a3/i/v-i-0…","video_id":"0275d5a2-6708-43a7-bd64-e4aae81aa813","player_id":"8ca46225-42a2-4245-9c20-7850ae937431","provider":"flowplayer","video":"Do The Yellow Vests Reflect The Broken Dreams of The French"}

“It affected us because [at] the opening people would discuss [our work] with us. We were young and revolutionary and had a lot of energy. Of course the occupation forces were completely against this association,” he added. “There were no rules for the soldiers who came into the gallery. Right-wing soldiers would come in and confiscate more than the liberal and left-wing soldiers. We could get some back but 90 percent of the work was lost.

“For a long time we had no offices. We felt that one association was not enough. We needed an organization and structure so we opened Gallery 1978 in Ramallah, which was the first gallery in the occupied territories,” Mansour said. “My little green car was practically the headquarters for years and the size of that car dictated the size of my painting. We had to create works that would fit in the car.”

Mansour says their perception of art changed during the Intifada, taking on a more critical, anti-establishment tone. Communication between the group and other artists in the country was often restricted, due to Israeli forces’ segregating the area and banning free travel among regions of Palestine.

To protest the occupation, Palestinian artists boycotted Israeli art suppliers, turning to earthworks and mixed media, using materials derived from the Palestinian environment. Restrictions on imports and free movement meant Palestinian art suppliers were short of basic materials like oil paints and canvas.

“Nabil worked on leather, Sliman and Vera with clay and hay and I used to work on wood I found in the trash,” Barakat recalled. “One day Nabil sold a work and a year later the buyer said there was a problem with the piece. His dog had eaten some of the leather and Nabil had to restore it.

“From that day we would say that Nabil makes hamburgers for dogs and that Silman makes biscuits for donkeys,” he joked. “We experimented with new choices for art. For example in 2008 when there was the war on oil. Everything was burning, so I chose to use fire and burning as my medium and mixed metal paint to use.”

New themes and iconography emerged in post-Intifada art. In addition to the peace doves, keys, olive and orange trees known to crop up, horses, gateways and various natural objects also took on new meaning.

“The prickly pear cactus [was frequently used], which was related to the destroyed Palestinian land,” Anani said. “All Palestinians used to plant it, but when the land was destroyed it still grew back so it became a symbol of the ruined land that would return.

“Most Palestinian artist also used the symbol of the beauty Palestinian women and embroidery,” he added, “which they felt was tied to their identity, culture and history.”

Despite the hardships, the artists remember their days of struggle fondly, if only for the determined driving forces behind the art movement and their depiction of Palestinian identity and culture.

“When we exhibited in the ’70s, there were no galleries ready for showing work or even a way to hang our work,” Tamari said. “The audience was different. There were students, teachers, housewives and laborers who would come and truly understand the work and symbols we were painting. People only used to want stories, to smell the olive trees we were painting.

“I feel like those days were better, when we used to display our work in El-Hakawati Theatre or Nablus’ municipal office, for example,” Mansour added. “There was a sense of value from the audience and they would debate with us and ask questions. There was more excitement.

“When our works get put in a museum nowadays, I feel happy,” he mused, “but I’m not as proud as I was when showing my work in Palestine.”

“Challenges of Identity” is up at Dar El Nimer, Clemenceau, until May 11.

This article has been adapted from its original source.