Shatila’s Memory Museum is no bigger than a bedroom. The water seeping through the walls has created rust-colored patterns along the peeling white walls, and a wooden board prevents rats from crawling into the ground-floor space.

Yet, the museum is cherished – not only as a monument to Palestinian heritage, but as an act of resistance.

“The Israelis took the land by force and now they are trying to take the traditions too,” founder Mohammad Khatib said.

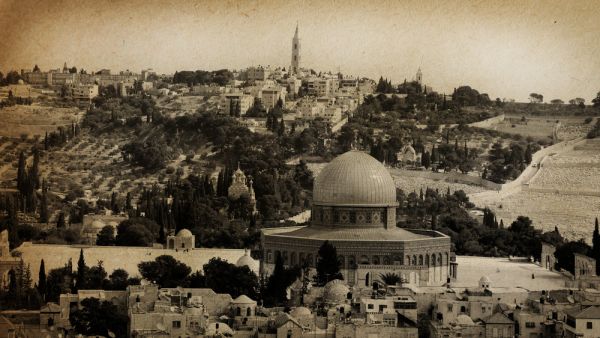

“They are saying that in the land [of Palestine] there weren’t any people. In reality, there were people with a history, a culture and traditions.”

Khatib went door to door to collect the objects Palestinians had brought with them during the exodus of 1948. The museum, opened in 2005, bears witness to the culture that existed prior to the Israeli declaration of independence, made 70 years ago this year on May 14.

“Everyone tries to keep those traditions alive however they can,” Khatib said. For his part, Khatib recounts the tales attached to each item in his collection, which includes keys to houses that were abandoned in 1948, agricultural implements, jewelry boxes and different kinds of jaroushe – a traditional coffee grinder that plays music as one grinds.

As some Palestinians in Shatila see it, May 15 will not mark 70 years since the Nakba; it will mark the 70 years of catastrophic events that have unfolded ever since.

Khatib is one of these Palestinians. Since he was carried to safety in Lebanon in his mother’s arms, destruction and violence have followed him. In 1973, his father was killed in Sidon by Israeli raids launched against several Palestine Liberation Organization targets across Lebanon. The next year, the Nabatieh camp where his family had found refuge was razed and its population dispersed.

A few years later, in 1982, members of the Lebanese Christian Phalange militia stormed Khatib’s newfound home in Shatila and the adjacent Sabra camp, killing at least 800 people as Israeli forces stood idly by.

An ax, framed and hung on the wall of the museum, bears witness to one of the many massacres that stain decades of Palestinian history.

Few people in the camp still remember what peace in Palestine looked like. Among them is 95-year-old Abou Ahmad Sarhani, whose communication of his memories is made difficult by a speech impairment and diminished hearing.

But he is not silenced.

“Palestine was mixed, both Christians and Muslims. There were an equal number of them and there was no difference between us,” Sarhani said.

“I was living like I’m living now, I had nothing. My parents were farmers – we had a house as small as this one. But I was happy because I was living in my homeland.”

On April 9, 1948, the family got word of a massacre taking place along the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv road, in the village of Deir Yassin.

Accounts of Palestinian women and children being shot down with submachine guns, of gold being confiscated and houses being mined with explosives, began filtering in.

“We were scared so we left, only for a bit, no one even packed their cloths or items. No one packed anything. ... We just walked out. It was supposed to be only a short visit,” Sarhani said.

Twenty-five years old at the time, Sarhani walked to Lebanon with his family and his fiancee.

The couple married in Lebanon and had 12 children and 40 grandchildren. None of them has since been able to return to Palestine.

“How long have I been here?” Sarhani asked rhetorically.

“They still call me a ‘refugee.’ Will I be able to erase the label of ‘refugee?’ It won’t get erased. It doesn’t get erased. I’m still and always will be a refugee.”

Recently, even that status has come under threat. The United States’ decision earlier this year to cut tens of millions of dollars of aid money to the U.N. Palestinian refugee agency, UNRWA, was fueled by Trump’s opposition to the Palestinian people’s right to still call themselves refugees. While despised, this status is also what entitles Palestinians to humanitarian aid and, most importantly, gives an internationally recognized basis from which to advocate for return.

Sarhani was invited as a speaker of honor to a rally held last week by the Children and Youth Center in Shatila, headed by a man known in the camp as Abou Moujahed.

“[The children] should all understand that they have the right to return. The camp is not the end, it’s just [temporary while] we are obliged to stay here as refugees,” Abou Moujahed told The Daily Star.

“They have to know that their country is occupied and learn about the U.S. and all the countries that support Israel.”

But recent developments have left Sarhani’s own offspring increasingly jaded about the future of Palestine. One of his eight daughters, Ahlam, said she had lost faith in the possibility of return.

“Palestine is different. Syrians can go fight in their own country, we can’t even do that. There is no hope. We can’t even dare stand at the borders,” she said, referring to the ongoing protests at the Gaza border with Israel that have seen demonstrators shot at and killed by Israeli forces.

Seventy years on, no end to the Nakba is in sight. “We lived through the war, we lived through the massacre of Sabra and Shatila. In this very house we had six or seven deaths. No one in this whole world has learned death as we have, or violence as we have. I say ‘we’ as the Palestinian people,” Ahlam said.

“Look how deep the tragedy runs here. A Palestinian can’t work as a garbage man under the Lebanese government – a garbage man that cleans up the citizens’ trash! We are not allowed to do that. We have doctors, we have engineers, we have educated people. But nobody lets us work.”

If any hope is left, it will be for the next generations, she said.

“Nobody will [free our land] except our people.”

This article has been adapted from its original source.